Dietary recommendations for middle-aged patients

Protein intake, especially from plants, in middle age has been associated with a higher likelihood of healthy aging and a positive mental and physical health status in women, suggests a recent analysis of data from the Nurses' Health Study (NHS).

The study is considered the first to examine the long-term impact of protein consumption in middle age. Intake of plant-based proteins was associated with a 20%–60% greater chance of not having limitations in physical function. Plant-based protein was also associated with a higher chance of good mental health.

Eating several meals a week with beans, peas, lentils, tofu, whole grains, or seeds is an easy way to increase plant-based protein in your diet, and these meals provide soluble and insoluble fiber that promotes gut health, as well as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory polyphenols and other phytochemicals.

In contrast, animal protein intake in middle age has been associated with an increased risk of premature mortality from chronic diseases, primarily cardiovascular diseases.

Therefore, it is advisable that middle-aged patients aim to meet or perhaps modestly exceed the recommended dietary allowance of protein of 0.8 g/kg per day and make plant protein a substantial component of their daily dietary protein intake.

Effects of protein intake in the elderly

In studies with elderly populations, lower protein intake has been associated with loss of lean mass. Studies of animal protein supplementation in the elderly have demonstrated gains in lean mass potentially related to amino acid composition.

In the body, dietary protein and exercise activate a pathway called rampamycin, which is reduced by aging, thus stimulating muscle protein synthesis and possibly improving physical function.

Regarding the differential associations of plant and animal proteins in healthy aging, Dr. Ardisson Korat and co-authors say that plant protein has been associated with favorable levels of important factors for protection against cardiometabolic diseases, such as reduced LDL cholesterol, lower blood pressure and insulin sensitivity, as well as decreased levels of pro-inflammatory markers.

Dietary recommendations during physical activity

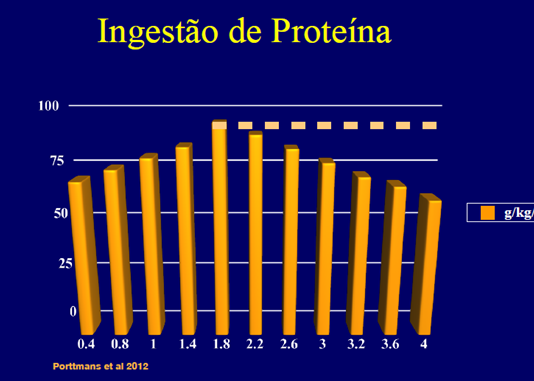

FAO/WHO estimates the protein requirement for adults at 0.8g/kg/day; these recommendations are focused on individuals with moderate or moderate intensity physical activity.

It appears that an average protein intake of 1.25 g/kg/day is sufficient to compensate for the increased muscle protein breakdown during prolonged exercise sessions.

According to the figure, in a study conducted with athletes, peak muscle production was achieved with protein levels of 1.8g per kg of body weight; above this value, a reduction in muscle production was observed.

Dietary recommendations for weight loss

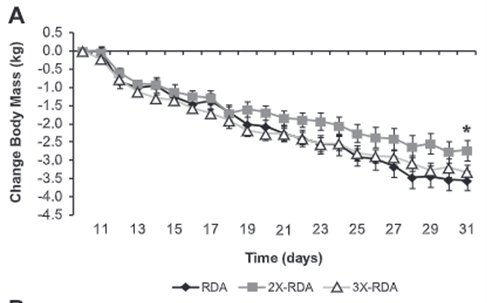

According to a study that separated participants into 3 groups: with protein intakes of 0.8 (recommended: RDA), 1.6 (2-RDA), and 2.4 (3-RDA) g/kg of body weight for 31 days. A 10-day weight maintenance period was followed by a 21-day weight loss period, and the following results were found:

The RDA group lost the most weight and muscle mass, while the 2RDA group lost the least muscle mass of the three groups (consuming 1.6 g of protein per kg of body weight).

In summary, they determined that consuming dietary protein at levels exceeding the RDA may protect fat-free mass during short-term weight loss.

Some disadvantages of high protein consumption.

On the other hand, the intake of total and animal proteins has been positively associated with increased insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), such as dairy proteins (from the famous whey protein), which is implicated in the growth of malignant cells in breast and prostate tissue.

Protein supplements are the best-selling products in the dietary supplement category. And whey protein, far from going out of style, is gaining more followers as the protein craze builds discourse and shapes habits.

In 2023, Brazil imported a staggering $54 million worth of whey. This podcast>> goes back to the origins of whey and discusses the usefulness of this supplement.

Studies in animals consistently show that high-protein diets are associated with more atherosclerosis. And some, but not all, epidemiological studies in humans also show a link between protein intake and heart disease.

A new article suggests that some of the problems observed with proteins may boil down to just one amino acid: leucine.

This study, published in Nature Metabolism, shows that protein intake leads to an increase in amino acids in the blood, and somehow one or more of these amino acids stimulate the activation of monocytes – inflammatory cells. Inflammation causes atherosclerosis and, eventually, cardiovascular disease.

Leucine is one of the three branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) found in whey protein. Many foods we eat contain leucine; examples per 100g of food:

- pork meat (2.88g)

- beef liver (2.67g)

- canned tuna (2.37g)

- skimmed milk powder (3.54g)

- mozzarella cheese (2.38g)

- sliced cheese (2.19g)

- eggs (1g)

- peanuts (1.54g)

- soja (1.36g)

- cashew nuts (1.29g)

- oats (1.28g)

Full table of leucine in foods at >>

To reach the recommended daily intake of 7.5g of leucine, it is beneficial to include food sources of both animal and plant origin, but with greater attention given to plant-based sources.

Another factor that should be highlighted is the competition between leucine and all BCAAs with tryptophan (the famous "feel-good" amino acid, capable of forming serotonin), so a diet rich in leucine or BCAAs can reduce our circulating serotonin, affecting mood and worsening depression.

Reducing protein intake may help control metabolic syndrome and some of its main symptoms, such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. This was shown in a study conducted by Brazilian and Danish researchers and published in the journal Nutrients.

The study showed that reducing protein intake to 0.8g per kg of body weight was sufficient to achieve almost the same clinical results as a calorie-restricted diet, but without the need to reduce calorie intake.

The results suggest that protein restriction may be one of the main factors leading to the known beneficial effects of dietary restriction. Therefore, a protein-restricted diet could be a more attractive and relatively simpler nutritional strategy for individuals with metabolic syndrome.

Sources:

DOI: 10.1096/fj.13-230227

DOI: 10.159/s0100-879x2012007500096

DOI: 10.37111/braspenj.2022.37.2.06

https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/1000179

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2016.05.010

https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2023.1269548

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2023.11.010

https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/14/13/2670

https://ojoioeotrigo.com.br/2024/04/o-milagre-do-whey/